The Algorithm Will See You Now: FDA's AI Leap and the Human in the Loop

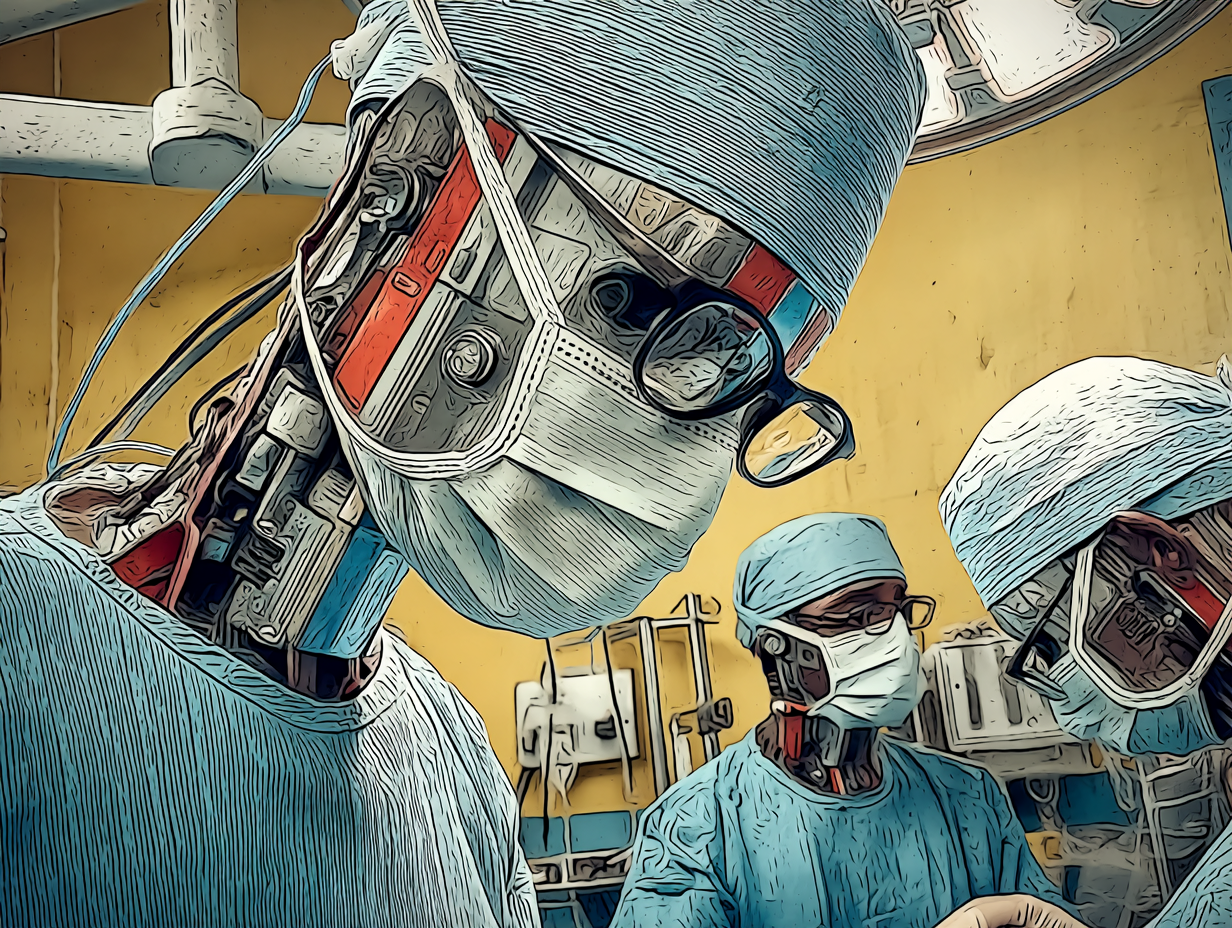

I was scrolling through my newsfeed, probably procrastinating on something far less interesting, when a headline from the FDA practically did a digital backflip to get my attention. They’ve just announced the success of their first AI-assisted scientific review pilot. They're also hitting the accelerator, aiming for an "aggressive" agency-wide AI rollout by June 2025. You can see the official fanfare on the FDA's announcement page. My first thought? "Well, that escalated quickly." It feels like just yesterday we were discussing AI in terms of slightly better spam filters, and now it’s getting a lab coat and a stethoscope.

On the surface, this is the kind of news that makes efficiency experts do a little dance. The FDA itself says these generative AI tools let their scientists "spend less time on tedious, repetitive tasks." One official even claimed it enabled them to perform tasks in minutes that previously took three days. Faster drug approvals? Less bureaucratic slog? Sounds like a win. My inner programmer from those early internet days, the one who built websites on Geocities thinking he was crafting the digital equivalent of the Pyramids, gives a quiet nod. Then the philosophical gears start turning, a familiar hum from wrestling with these kinds of questions, the sort I delved into when writing "Keep Your Day Job". The big question starts flashing in neon: when do we, as a society, decide that a human is no longer necessary in the loop for decisions that carry significant weight, decisions that touch upon our health, our ethics, our very lives? Drug approval is a monumental responsibility. Are we ready for a future where the final say, or even a critically influential say, comes from silicon?

It's a fascinating turn because the FDA itself, just a few short months ago, seemed to be singing a slightly different tune, or at least a more cautious one. In documents outlining their approach to AI, such as their paper on "Artificial Intelligence and Medical Products," the emphasis was clearly on responsible and ethical development. They spoke of AI systems working based on "human-defined objectives" and fostering a "patient-centered regulatory approach" through collaboration. This implied, to my reading, a human firmly grasping the reins, or at the very least, being an indispensable part of the oversight. Another draft guidance from January 2025 on using AI for regulatory decision-making for drugs also stressed establishing "model credibility" for a "particular context of use," hinting at careful, human-led validation.

The shift, or perhaps the accelerated pace, makes me think of something I explored in my book: the allure of technological solutionism. AI can indeed be a powerful tool, a sophisticated intern that never sleeps, a digital Sherlock Holmes sifting through data for clues. Yet, the risk is that its efficiency can dazzle us into ceding judgment in areas where human nuance, empathy, and ethical reasoning are not just beneficial, but vital. It’s like giving a super-fast car to someone who’s only ever ridden a bicycle; the speed is thrilling, but the control needs to be learned, and the potential for unforeseen consequences is magnified.

This isn't just an FDA-specific thought bubble. A few years back, the Harvard Gazette published a rather insightful piece (though a few years old, its points are more relevant than ever) highlighting the mounting ethical concerns as AI takes on bigger decision-making roles. They pointed to the classic AI anxieties: privacy, surveillance, and the insidious problem of bias baked into algorithms. But the article also zeroed in on what it called "perhaps the deepest, most difficult philosophical question of the era, the role of human judgment."

And that, for me, is the core of it. Can a machine truly understand the ethical weight of approving a new drug that might save thousands but harm a few? Can it navigate the gray areas where data ends and wisdom begins? Proponents will argue that AI can be more objective, free from human fatigue or personal prejudice. And there's some truth to that; we humans are gloriously fallible creatures, prone to bad days and cognitive biases. I've seen enough pop culture portrayals of rogue AIs, from HAL 9000 in "2001: A Space Odyssey" (a film that still gives me existential shivers) to the more overtly hostile Skynet from the Terminator franchise, to know the common fears. But I've also seen enough real-world examples of algorithmic bias in hiring, lending, and even criminal justice to understand that AI is often a mirror reflecting the flaws in the data we feed it, flaws that originated with us. An algorithm trained on historical data that reflects societal biases will, quite logically, perpetuate those biases, just with terrifying speed and scale.

The move by the FDA feels like a significant step across a threshold. It’s presented as a way to clear a backlog, to speed up science. And speed can be good; patients waiting for life-saving treatments would certainly agree. But what if speed comes at the cost of deep, contemplative human oversight in areas where the stakes are profoundly human? There's a difference between an AI helping a scientist sift through mountains of data, highlighting anomalies a human might miss, and an AI making a recommendation that carries the implicit weight of approval, subtly influencing the human who is technically "in the loop" but increasingly reliant on the machine's output. The "human in the loop" could become a "human rubber-stamping the loop."

Letting go of the human element in critical decision-making isn't just a practical question of risk assessment; it's a philosophical one. It speaks to what we value. Is it pure, unadulterated efficiency? Or is there an intrinsic worth to human judgment, even with its imperfections, when the well-being of other humans is on the line? This isn't about being a Luddite or fearing progress. I’ve spent a good chunk of my life building and championing technology. The FDA’s "aggressive rollout" will be one to watch. As they integrate these powerful tools, the real test will be how they navigate this tension, ensuring that the pursuit of efficiency doesn’t inadvertently sideline the essential, irreplaceable element of human accountability and ethical deliberation. It's a debate as old as the first automated loom, really. The Luddites, back in early 19th century England, weren't just smashing textile machines because they were technophobes having a bad hair day; they feared a future where their hard-won human skills, and by extension their livelihoods and sense of agency, were rendered obsolete by relentless mechanization. We see echoes of this anxiety in countless sci-fi narratives that wrestle with the soul of the machine, or lack thereof. Think of Philip K. Dick’s work, constantly questioning what it means to be human in a world increasingly populated by sophisticated androids. Or consider Minority Report, where the "pre-cogs" offered seemingly infallible predictions of future crimes, leading to arrests before any crime was committed. It’s a system built on the altar of efficiency and pre-emption, yet it was profoundly flawed, vulnerable to manipulation, and utterly devoid of nuanced justice or the possibility of redemption. The film, based on a Dick story, brilliantly shows how an over-reliance on a "perfect" system can trample human rights.

This isn't just about preventing Skynet from achieving sentience and deciding humanity is a particularly inefficient virus that needs deleting. It's about the more subtle erosions of human judgment in less apocalyptic scenarios. The classic 'Trolley Problem' in philosophy, where you're asked to decide whether to pull a lever to divert a runaway trolley, saving five lives but actively causing the death of one, gets a turbo-boost in the age of AI. Who programs the ethical subroutines for the autonomous car that must, in a fraction of a second, choose between swerving into a pedestrian or risking its passengers? Is it a purely utilitarian calculation – the greatest good for the greatest number? And who is accountable when the algorithm, however meticulously designed and well-intentioned, makes a choice that results in tragedy, perhaps a choice a human, with all their messy emotions and intuitive leaps, might have avoided? The "computer says no" trope from Little Britain is funny when it's about a bank loan; it's terrifying when it's about life and death. Because when it comes to our health, I, for one, still want to know there’s a thoughtful human, not just a brilliant algorithm, pondering the consequences.

What do you think? Where do we draw the line, or should we be drawing new ones altogether?